Local talents come together to create a world-class Museum of the American Arts and Crafts Movement

By Judi Shade Monk

Jan. 14, 2022

Architecture, Crit, Editor’s Picks, Southeast

On the Florida peninsula’s central west coast, just across the bay from Tampa, is the city of St. Petersburg, a recurring New York Times pick for best places to visit in the world. Indeed, “St. Pete,” as it’s called by locals, has a lot going for it. As the state’s greenest urban center, St. Pete is on track to reach 100 percent renewable energy by 2035. It also boasts a well-established arts community, which has spurred the city’s cultural patrons to invest heavily in pilgrimage-worthy works of architecture. The latest, the Museum of the American Arts and Crafts Movement (MAACM), is arguably the crown jewel of the bunch.

Situated on a 3.2-acre site where downtown meets the Waterfront Arts District, MAACM is the third privately funded cultural institution in St. Pete and houses a renowned collection of American Arts and Crafts objects owned by the Two Red Roses Foundation. Designed by local, Ybor City–based office Alfonso Architects, and brought to life by construction management firm Gilbane, the 137,000-square-foot, $90 million project offers an architecture both sensuous and rational, playful in its suspended white metal shingle–clad geometries and elegant in its proportions and layered, handcrafted materials. The precisely executed detailing never deviates from the overarching design logic; simply put, its consistency and quality are world-class.

The hundreds of small and large works on display feel right at home in this gracious and considered context, which is positively spartan compared with the flowery interiors that exemplified the Arts and Crafts movement. Here, each ornate museum piece—be it pottery, block prints, or painted glass—is afforded the opportunity to shine and be marveled at. The greatest challenge for fellow museum nerds, and particularly for museum nerds who happen to be architects, is pacing oneself as one moves through the 40,000 square feet of galleries. A visit is both exhilarating and mentally exhausting, impossible to complete in a single day.

A towering sculpted stair dominates the full-height atrium. (Seamus Payne)

Mottled black Venetian plaster marks out critical thresholds throughout the interior, offering a counterpoint to the gleaming white shell—also plaster, but looking for all the world like Calacatta marble—of a sculptural stairway that connects the galleries starting on the second floor. A long stretch of the opening gallery is glazed, allowing visitors to orient themselves prior to immersion in the collection. Elsewhere, small openings punctuate the otherwise-opaque exterior envelope. South-facing windows offer views of an ever-increasing number of residential towers, while those on the opposite end of the building frame a bustling low rise commercial corridor and the Crescent Lake water tower, a local landmark since 1924. On the top floor, afternoon sun falling through a clerestory casts a mesmerizing bar of light across the exhibition space.

The inner side of the stair is paneled in rich walnut. The quarter-sawn white oak steps glow with light. (Seamus Payne)

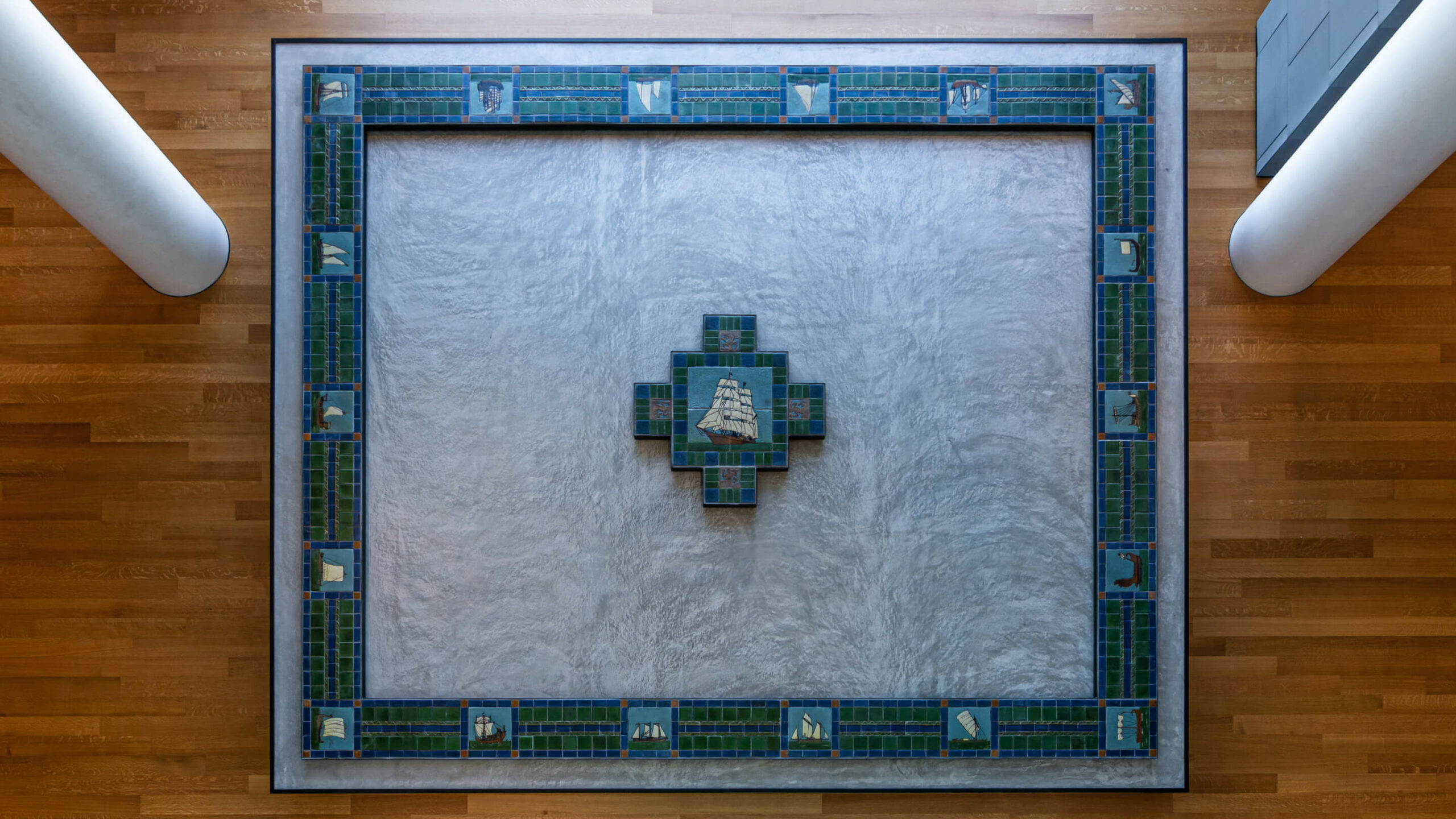

But one’s itinerary could just as easily begin and end in the soaring full-height atrium, which contains the museum store and a cafe, in addition to administrative offices. From here, it’s possible to admire the spectacular stairway from all angles, including below; its tightly coiled form is a subtle homage to Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Glasgow Rose motif (titular inspiration for the Two Red Roses Foundation?). The east face of the atrium is clad in walnut acoustic panels, which have clearly been laid with great care. Along the base of the wall is anchored one of the museum’s many gems: an intricate 600-piece mosaic that portrays a calm maritime scene dating to 1914.

Like these architectonic elements, the coffered skylight underscores the architects’ commitment to evoking the ethos, if not the style, of the Arts and Crafts movement. To create the installation, they stacked and offset metal louvers in a manner recalling patterns found in Frank Lloyd Wright’s stained-glass works, examples of which are in MAACM’s collection. (The skylight transept brilliantly conceals a maintenance catwalk.) An expanding and contracting overlay of light and shadow enlivens the atrium’s rich finishes over the course of the day. Museum patrons and the general public are welcome to watch or to dine in the cafe and linger in the comfort of Tulip tables and chairs. Or they might browse the thoughtfully designed and curated gift shop, where daylight is modulated by an exterior cast-in-place concrete brise-soleil.

The scale of the museum both anticipates changes in the urban fabric and responds to the scale of the city’s past, taking confident cues from the historic former Pennsylvania Hotel across the street and the nearby Coliseum Ballroom and Palladium Theater. Given MAACM’s four-sided site, as is typical in car-centric Florida, the design team elected to break up the program into dedicated volumes. The five-story museum block anchors the western edge, while a more diminutive block containing an upscale restaurant and event space acts as a bridge to the parking structure. With its Brazilian granite rainscreen, the museum appears weightier than the mostly glazed restaurant annex, which compensates with a dramatic roof canopy that pins the garage behind it.

MAACM displays hundreds of mosaics, furniture, stained glass, and other objects, which represents a mere sampling of its total collection. (Joe Brennan)

Before MAACM opened in September 2021, much of the local media coverage dwelled on the extensive project delays, partly due to COVID-19. A positive spin would foreground the patience and vision that has produced an architectural reminder to not rush something intended to last forever. It’s also a reminder of what an extraordinary client–design team–contractor collaboration can yield and, still more, how regional expertise often exceeds the products of many an anointed starchitect. Just as our universe is packed with constellations, some celebrated for millennia and many more unknown, world-class practitioners in every region are waiting to be seen. We must do better to acknowledge extraordinary practitioners—not as “second-tier starchitects,” as a 2010 article referred to Brad Cloepfil and Allied Works, but as the stars they are when we first catch sight of them. Alfonso Architects’ MAACM makes a most compelling case that our stars are bright in Florida.